Writing Essentials

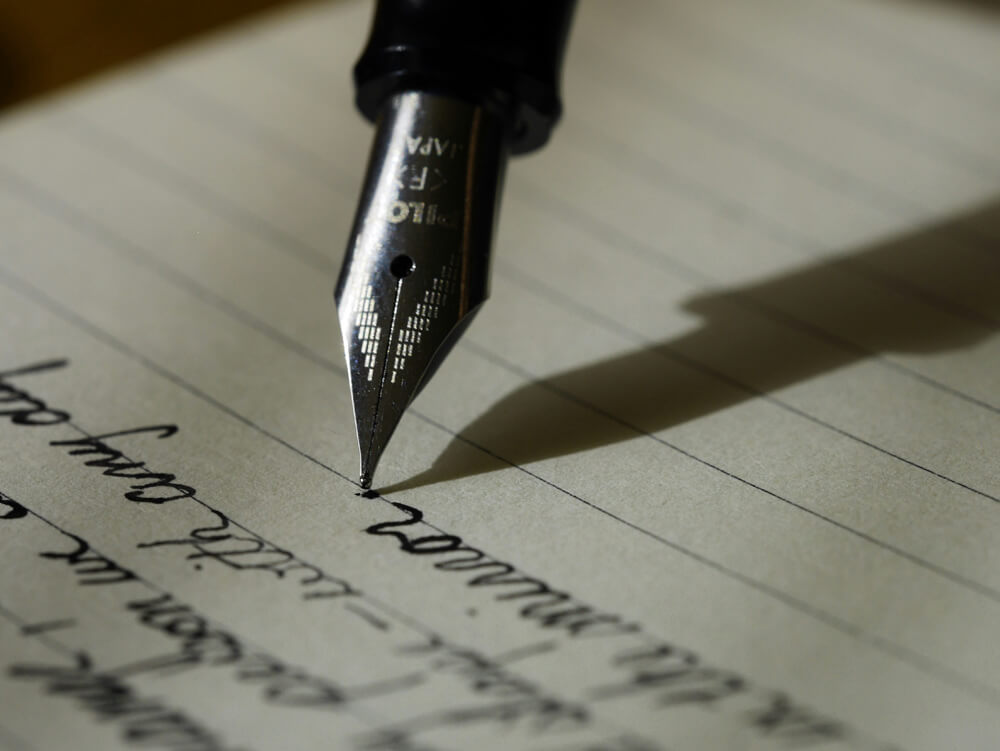

The Creative Process Behind Poetry: A How-To Guide

Do you wish to be the next William Wordsworth? Recite tear jerking poetry to an unrequited love and make them fall in love? Would you like to express your words as easily as taking a breath? Well, I've got you covered with my how-to guide on writing poetry.

Well, I might be tooting my own horn, but as a fellow aspiring poet, I'd love to share how I at least write poetry that makes those satisfying connections line up in my head and make lovers swoon…

DISCLAIMER: I think poetry is not something that should be methodical (I know, how ironic that this is a 'How-To Guide').

I simply want to share the creative process that I have found works for me which may benefit you in some way.

Final Thoughts: Enjoy the Process

I don't believe there is a right way to write poetry. To me, it's about delving into areas you tend to avoid or neglect and make them into something beautiful.

My most important piece of advice is to enjoy the process and be mindful of what poetry brings you – it can be the most wonderful tool.

By Lily

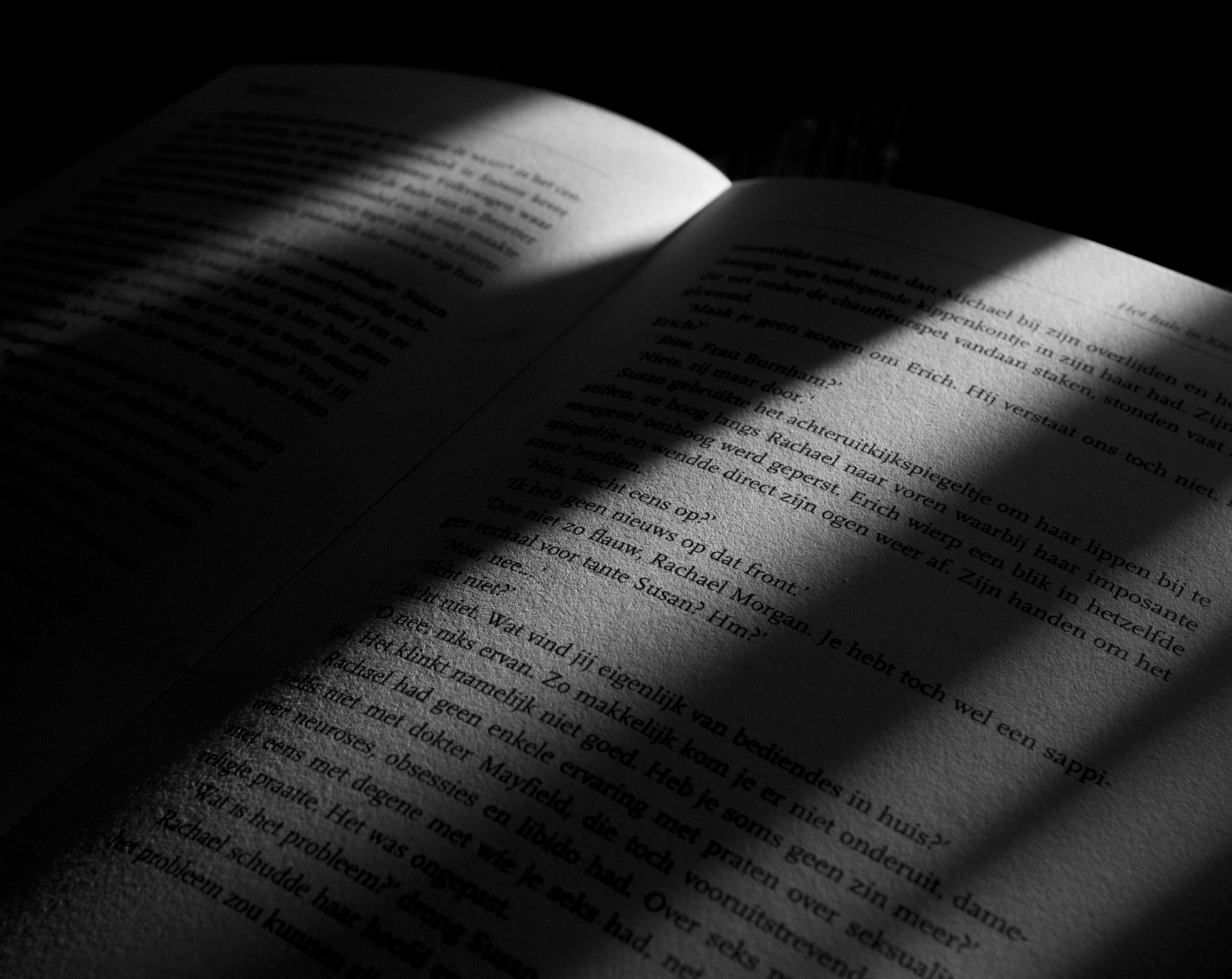

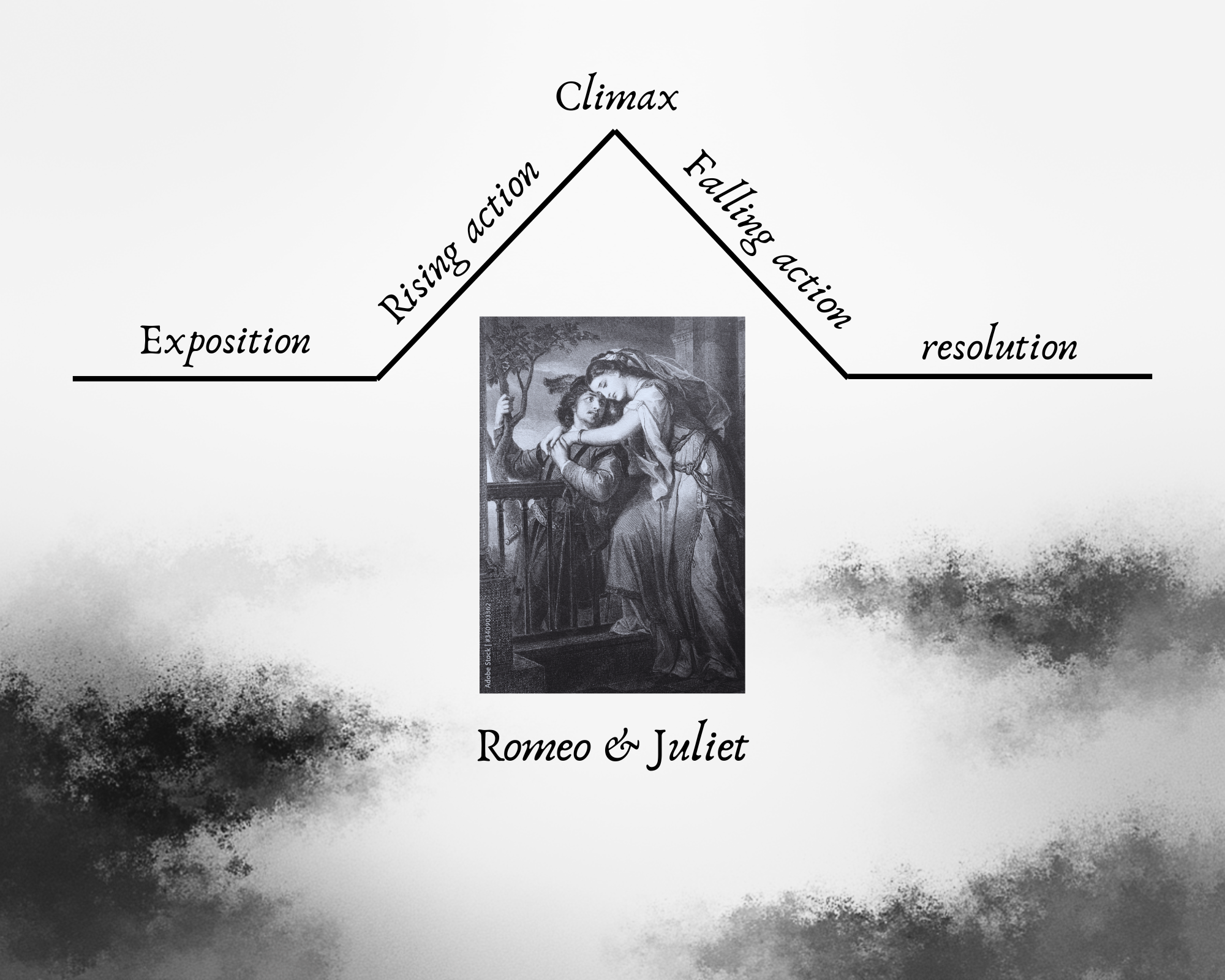

How to Craft a Story Structure

Story structures are the way in which a plot is told to the reader, and when it comes to storytelling, we've been taught from a young age that there has to be a beginning, a middle, and an end.

But there is much more to a story than that.

Writing may be a creative and artistic process, but structuring a story more closely resembles a scientific process or a cooking recipe, which, if you master, will make you a better writer.

Final Thoughts

Story structures are the skeleton every story needs. It's crucial for writers to understand how structuring improves writing for books, short stories, and even narrative poetry.

Though you don't need to necessarily adhere to it once created, a story structure can give you a foundation to fall back on and smaller goals to work towards.

And as with all literary techniques, once you know them, you can creatively dismantle them to your advantage.

By Rebecca