“Perhaps in the end, it was fitting, for his master was ever in love with misfortune and believed the world a wounded thing that can only be healed by story.”

Overview

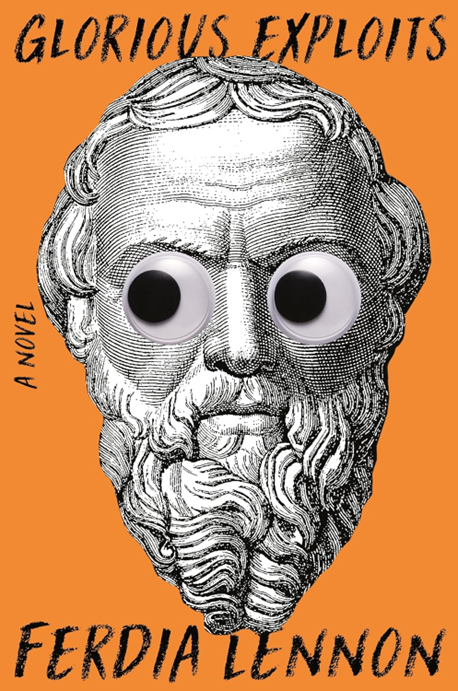

In 2024, Ferdia Lennon’s Glorious Exploits won the Waterstones Debut Fiction Prize, and it’s no wonder why. The blend of dark Irish humour and Greek mythology presents a unique, almost absurd voice to storytelling.

This novel depicts two unemployed potters, Lampo and Gelon, who, amidst a war-torn Sicily, decide to put on a show. They aim to produce a performance offering to feed any Athenians who can recite words of Euripides, but soon this passion project becomes larger than they anticipated, and a full-blown production of Medea is in motion.

If this blend of Greek reimagining and dark Irish humour appeals to you, find it here:

Black Humour and Tone

The first person narrative is quick to read and something completely unexpected from the premise. I went into this book believing it would feature antiquated language, but instead found myself laughing at the opening passage. This is something Lennon balances well throughout the novel: the blend of historical, war-torn emotion and breezy comedy. In this way, it feels believable that the reader is transported to Ireland through the colloquial tone, while simultaneously being taken to Sicily in 400s BC.

The complete shift from subject matter to tone is a regular occurrence throughout the novel’s duration, and discovering that this was a debut novel was surprising. It is written with the confidence of a writer well established in their voice — and it is a refreshing one, at that!

War and Tension

As for the war elements of the novel, these are demonstrated through the complexities of staging the play in an area that despises Athenians. Through Numa’s performance of Hecuba, he is attacked by an onlooker, Biton, and, alongside other performers, is killed. This devastating shift from laughter at the failures of the actors, and mocking jokes like: “Look, there are the Athenians, and they’re shite!” to full-blown violence against them eight pages later, came as a shock to me. Although the hatred between them was clear, the Athenians being banished to the quarry in the first place was an indicator — the on-page attack was sudden.

There is similarly a tension between Lampo, Gelon, and the Athenians, as well as between Lampo and Gelon themselves. To the Athenians, they represent the hatred that has been directed towards them as outsiders; they are fearful and never fully trusting, going along with the production in order to be fed. Lennon writes: “the prisoners stare at us like chained kings as we roll by,” emphasising the difference in status and therefore power between the two groups. Beyond this, Gelon and Lampo fight at several points throughout the book, showing that interpersonal relationships are complex, no matter where you come from or which group you are labelled alongside.

Poverty and Performance

One of the main aspects of Glorious Exploits is the perseverance of people in times of war, with coping mechanisms often taking the form of the arts. This is something deeply entwined with the characters’ childhoods. Both Gelon and Lampo have a passion for poetry; after selling their families’ goods (and getting in a lot of trouble for it), they read the first book of The Odyssey. Lampo recalls: “For a while I didn’t care I was poor, or that Ma and I were alone ‘cause my da did a runner, […] I didn’t care about anything but the words he was saying.”

This formative moment highlights the importance of art to the characters and their friendship, as this flashback determines Lampo following Gelon to the ship — which is an integral plot element in the novel.

This love for the dramatics, despite social status, is embodied in Lyra, Lampo’s love interest (and Dismas’s slave). Her song emphasises the ties that Lampo feels between life and art. Lampo, being the presumed mouthpiece of Lennon, writes: “The voice isn’t beautiful, and at first, I’m disappointed, yet as the words tumble out, I feel a tingling on my skin because there’s a wildness to it — an uncommon thirst for life and other things.”

This quote elucidates that art doesn’t have to be perfect to be felt, and that most of the time, when it is the most authentic, it feels the most passionate. For example, “It’s not the moon moving them, but the mad shepherd who’s forgotten who he is,” represents Lampo, the unemployed potter becoming a producer because he feels the call to art in a time of need. The moon is often a literary motif for a muse or inspiration, typically a feminine one, once again linking Lyra to Lampo as a muse.

Conclusion

Overall, I was surprised by this book and my almost-instant connection to the characters. The clear love for the dramatics, as well as Greek mythology and storytelling, is evident throughout, and I really appreciated Lennon’s original approach. The balance of tone is sustained for the duration of the novel, and I found a “tingling on my skin because […] [of the] wildness to it.”

However, despite this shared, vehement love for the arts, I still felt there was something missing. I didn’t quite get five- (or even four) star tingles, and therefore, this book sits comfortably at a three-star rating.

Have you read this book?

We would love to hear your thoughts on this book, perhaps you agree with our review, or, disagree?